As a clear example of Merce Cunningham's choreography, philosophy and originality, I think it deserves a place in the list.

Background

|

| John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Robert Rauschenberg, London 1964. Photo: Douglas H. Jeffrey |

Born in 1919, Cunningham moved to New York in 1939 to join the Martha Graham Dance Company, one of the major non-ballet dance companies of the time, as a dancer (he has often been named onf the best American dancers of the 20th century). He presented his first choreographies in 1944. Over a career that included collaborations with some of the biggest names in contemporary art and music, most famously his partner John Cage, he created over 200 dance works until he died at the age of 90. Cunningham was always at the vanguard of his art, and BIPED, created in 1999 when Cunningham was 80, is evidence of his constant pushing of the boundaries and search for the new.

BIPED is a work for 14 dancers whose duration is forty-five minutes. Cunningham worked on the choreography during 1997 and 1998. Parts of it were presented at the Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival in Massachusetts during the summer of 1998 as a work in progress. The first performance took place at Cal Performances' Zellerbach Hall on the UC Berkeley campus in April 1999.

The Cunningham philosophy

With Merce Cunningham, dance exists for its own sake: it is not slave to a narrative it has to convey, or to the music it has to follow. All the elements of his pieces are independent and not there to illustrate each other. The movement in particular is created on its own, and can be enjoyed on its own.

One of the consequences of this view is that the music, costumes, set and choreography of Merce Cunningham pieces were created independently, often coming together at the dress rehearsal only. On first working with composer John Cage, he said 'we could agree on a common structure for a particular dance and John could compose to that structure and I could choreograph. In the beginning, there were points in that structure where the music and dance came together. But later we abandoned that and made them entirely independent.'

To the instigation of Cage, Cunningham also used chance operations to formulate the elements of his pieces: tossing coins or using the I-Ching, he would determine the number of sequences, the length of the piece, the directions the dancers would follow in the space etc. From 1989, he even used a software called LifeForms (now DanceForms) to create sequences of movements, sketching out and mixing choreographic ideas on a computer before getting his dancers to execute them.

Who did what

Choreography: Merce Cunningham

Music: Gavin Bryars, Biped

Décor: Paul Kaiser, Shelley Eshkar of OpenEndedGroup

Costumes: Suzanne Gallo

Lighting: Aaron Copp

The music

The music Biped is by Gavin Bryars. It features violin, cello, electric guitar, double bass, electric keyboard and pre-recorded tape. There is a live and sampling element to it, with digital replication being used, and it creates 'an immense aural space' (The Guardian).

On his website, Gavin Bryars describes the process of creating it:

'It is one of the first new musical compositions commissioned by [Merce Cunningham] since the death of John Cage in 1992. In working on the music Merce and I agreed that we would follow the method established between himself and John Cage of working independently but towards a common goal, thereby avoiding any planned one-to-one relationship between music, dance and decor, but working to the same overall programme length, here 45 minutes. Merce and I did exchange faxes to give each of us pointers as to the other's thinking, and I did see examples of the animation techniques which were to form the work's design. When I asked if he had ever spoken with John Cage in advance about the work's structure and form (how many sections, whether dancers formed duos, trios, quartets ensembles and so on) he said that he always did, but equally that John always ignored the information.'

The decor

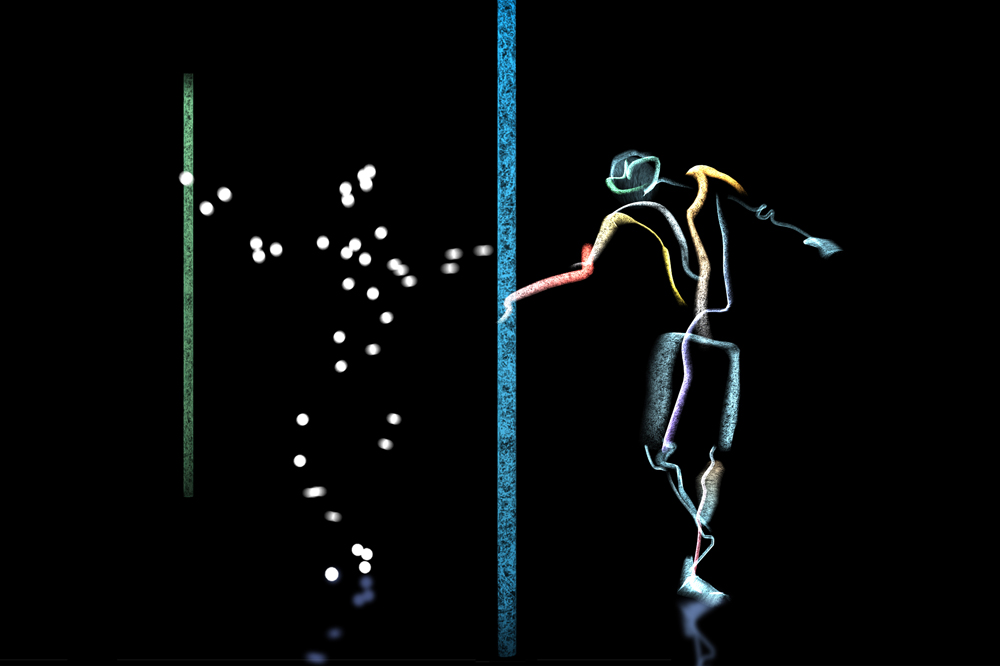

BIPED is probably most famous for its integration of technology, in the shape of projections of digital, animated dancers onto a transparent scrim at the front of the stage.

In 1997, designers Paul Kaiser and Shelley Eshkar had invited Cunningham to collaborate with them on a virtual dance installation called Hand-drawn Spaces. The BIPED designs owe a lot to it.

As a result of this collaboration, Cunningham invited them to work on BIPED, only telling them that the work would be 'about technology' and 'like flicking through channels on TV'. They decided to develop what they had created for Hand-drawn Spaces, using projections on a scrim and designing different sequences of animations running for a few seconds to four minutes each, whose order was determined by chance following Cunningham's request.

Cunningham choreographed three dancers (Jarred Phillips, Jeannie Steele, and Robert Swinston) whose movements were recorded using motion-capture technology. These resulted in four different representations of the body: hand drawn, dot bodies, stick bodies and chronophotograph bodies (I am linking to an image of it as it is hard to describe!). They veer towards abstraction, looking like phantom dancers performing in the ether. The colours and brush stroke-like lines used to represent them also give them a DNA feel, especially when we zoom into a detail. The result may feel slightly dated to some people, but what works is that the projections are not distracting, do not impede on seeing the real dancers, and it really adds an extra dimension and presents a new reality.

Aaron Copp, the dance company's lighting designer, devised the lighting, dividing the stage floor into squares and adding bars of lights that expand and contract, as well as 'the curtained booths at the back of the stage that permit the dancers seemingly to appear and disappear' (MCDC website).

Funny fact: 'By a miracle of chance operations, one of the first dancers on stage (Jeannie Steele) was haloed in a projection of her own motion-capture — “as if I were dancing inside myself,” she said afterwards.' (OpenEndedGroup website)

The costumes

The costumes, red-and-blue, silvery and shiny, were created by Suzanne Gallo, who had originally joined the company in 1982 as a wardrobe supervisor. The cliche of a Cunningham costume is the unitard, but Gallo managed to create 'handsome, sometimes luminously pretty costumes that allowed the body to move and captured the often intangible qualities of Mr. Cunningham's dances without intruding on the choreography itself.' wrote the New York Times in her obituary (she died in 2000, aged 46). This description fits perfectly to what she created for BIPED.

The shiny element of the costumes was necessary to help the dancers and choreography stand out behind the front screen.

The choreography

|

| Photo Tony Dougherty |

BIPED is a perfect example of the Cunningham style and technique: the very articulate torso (unlike ballet, Cunningham used the torso and bent it forwards, backwards, sideways), the legs not always turned out, the density of movement, the change of rhythms. The New York Times has a brilliant video dissecting one of the sections that is worth checking out. It is also characteristic of Cunningham because of its lack of story line or characters. The audience is left to make of it what they want to.

Cunningham has written: 'The dance gives me the feeling of switching channels on the TV.... The action varies from slow formal sections to rapid broken-up sequences where it is difficult to see all the complexity.'

In her review of the NY premiere, Anna Kisselgoff from the New York Times wrote: 'From their first bare-legged entry, usually as soloists or in small groups, the dancers announce the powerful carved shape of the choreography. Heads are thrown back, arms bent up but not quite curved, legs shoot out or are pushed into the ground with surprising force.' There are solos followed by simultaneous duets, lines of dancers appearing and disappearing in the darkness. She also noted the tension between unity and disunity in the patterns. The beginning of the video above shows it clearly.

Overall, in BIPED, nothing is as simple as it seems. Combined with the decor and music, BIPED's choreography takes on a particular dimension and feel, almost like an elegy. I was lucky enough to see the final performance of Merce Cunningham Dance Company in London in October 2011, and BIPED was the last piece on the bill - it made for quite a moment! To me the dancers in this work became the last guardians of the Cunningham temple, who would carry on performing for ever in some other parallel world. Our memories, perhaps.

What they say

'The company appear like gleaming, magical creatures, creating shapes that are at once abstract and full of emotion. It is utterly beautiful and entirely mysterious, the most eloquent testimony to a man whose works simply are what they are: potent, questioning and revelatory.' Daily Telegraph

'Above all, and most surprising from a man of 80, BIPED looked fecund, abundant, a cornucopia of poetic invention.' New York Times

'A major development in the art of stagecraft. It was a meeting of the latest computer technology and a venerable dancemaker's inquisitive mind.' San Francisco Chronicle

Sources

Review of BIPED, New York Times 1999 [link]

Review of BIPED, San Francisco Chronicle 1999 [link]

The Dancing Master, The Guardian 2007 [link]

Merce Cunningham Dance Company website [link]

Review of BIPED, The Guardian 2000 [link]

Review of BIPED, The Observer 2000 [link]

OpenEndedGroup BIPED essay [link]

Video: Dissecting a dance, New York Times 2009 [link]

Gavin Bryars website [link]

1 comment:

I just wanted to thank you for doing such a marvelous job on this...incredible details here on Merce's piece with compelling analysis. Love it!

Charemaine

Post a Comment